A dimension is a measurement of space. In a three-dimensional world, we usually think of three different directions as we measure the space in which we exist—length, width, and height. To indicate a certain location in space, we would provide three different coordinates on three different axes (x, y, and z).

The understanding of different dimensions is crucial in understanding much of mathematics. The ability to visualize and a flexibility in adjusting to n-dimensional worlds is a skill worth pursuing.

Portraying Three Dimensions

Even though most everyday experience is in three dimensions, most high school mathematics takes place in a two-dimensional world in which there is only length and width. Part of this is because traditional learning is largely communicated through books or on a chalkboard. Book pages or the planes of chalkboards have primarily two dimensions. Even if there is a picture in a book of a three-dimensional object, the object is “flattened” so that its likeness can be communicated through a two-dimensional medium. This can cause differences between what we see in a three-dimensional object and how the object is portrayed in two dimensions.

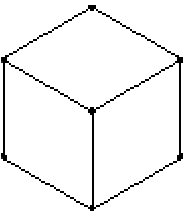

For example, consider a cube. In real life, a vertex of a cube is formed when three 90° angles from three different square faces intersect at a point.

However, in a two-dimensional representation of a cube, the right angles may measure other than 90° on the page. For example, in the picture of the cube below, each angle around the center vertex measures close to 120°.

The image of the three-dimensional object must be altered this way in order for it to give us the perception that it is really three-dimensional.

Portraying three dimensions in two-dimensional representations can also play tricks with our sense of perception. Many optical illusions are created by taking an impossible figure in three dimensions and drawing a two-dimensional picture of it.

Artist M. C. Escher was a master of communicating impossible ideas through two-dimensional drawings. In many of his engravings, the scene is impossible to construct in three dimensions, but by working with angles and making a few simple alterations, Escher fools our normally reliable sense of perception.

Imagining Dimensions

Points, lines, and planes are theoretical concepts typically modeled with three-dimensional objects in which we learn to ignore some of their dimensions. For example, earlier it was stated that a piece of paper or a plane is primarily two-dimensional. Although a piece of paper clearly has a thickness (height), albeit small, we think of it as being two-dimensional. So when considering objects with different dimensions, we must be able to visualize and think abstractly.

When we think of a plane, we start with a sheet of paper, which has length, width, and a very small height. Then we imagine that the height slowly disappears until all that remains is a length and a width. Similarly, when we draw lines on a chalkboard, we know that the chalkdust has length, a small width, and even an infinitesimal thickness. However, a mathematician imagines the line as having only one dimension: length. Finally when we consider a point in space, we must imagine that the point is merely a position or a location in space: that is, it has no size. To imagine a point, begin with an image of a fixed atom in space that is slowly melting or disappearing until all that remains is its location. That location is a true mathematical image of a point.

A college professor gave the following way to think about dimensions.

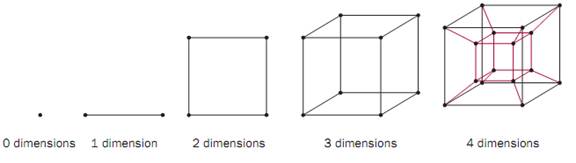

Start with a figure of zero dimensions: that is, a point. Set two of these items next to each other and connect them with a line segment. You now have a new entity of one dimension called a line segment. Again set two of these line segments next to each other and connect them with line segments. You now have a two-dimensional entity called a square. Connect two squares, and you have a three-dimensional entity called a cube. Connect the vertices of two cubes and you have a four-dimensional entity sometimes known as a hypercube or tesseract.

If you are having trouble visualizing a tesseract (as shown above), keep in mind that you are looking at a twodimensional picture of something that is four-dimensional! Even if you build a three-dimensional physical model of a tesseract, you will still need to imagine the missing dimension that would bring us from three dimensions into four.

Abbott’s Flatland

Imagining worlds of different dimensions is the premise of Edwin A. Abbott’s book, Flatland. He describes an entire civilization that lives in a world with only two dimensions. All of its inhabitants are either lines, or polygons such as triangles, squares, and pentagons. These individuals cannot perceive of anything but length and width. Imagine, for example, living in a blackboard and only being able to move from side to side or up and down. Depth would be an unknown quantity.

Abbott’s book describes a day when a sphere visits a family in Flatland.

Because Flatlanders are unable to perceive a third dimension of depth, they are only able to perceive first a point (as the sphere first entered their world), then a small circle which increases in area until it reaches the very middle of the sphere, and then a circle of decreasing area until it becomes a point again. Then it disappears. Imagine trying to communicate to these Flatlanders anything about the third dimension when they had never experienced anything in that realm.

Use a similar analogy when thinking about what four dimensions might be like. Even if a creature from the fourth dimension visited us here in threedimensional “Spaceland,” and tried to describe the fourth dimension to us, we would not be equipped to understand it fully.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland. New York: Penguin Books USA, Inc., 1984.

Berger, Dionys. Sphereland. New York: Crowell, 1965.

Escher, M. C. M. C. Escher, 29 Master Prints. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1983.

Rucker, Rudolf v. B. Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1977.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة