Congruency, Equality, and Similarity

المؤلف:

Konkle, Gail S

المؤلف:

Konkle, Gail S

المصدر:

Shapes and Perception: An Intuitive Approach to Geometry

المصدر:

Shapes and Perception: An Intuitive Approach to Geometry

الجزء والصفحة:

...

الجزء والصفحة:

...

7-1-2016

7-1-2016

2231

2231

What does it mean to say that one square is “equal” to another? It probably seems reasonable to say that two squares are equal if they have sides of the same length. If two squares have equal areas, they will also have sides of the same length. But although “equal areas mean equal sides” is true for squares, it is not true for most geometric figures.

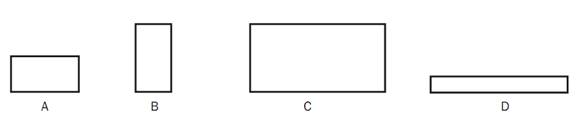

Consider the rectangles shown below. The areas of A and B and D are all 2 square units, but it is not reasonable to say that rectangle A “is equal to” rectangle D, although their areas are equal.

Geometry has a special mathematical language to describe some of these relationships. If Rectangle B is moved, turned on its side (rotation), and slid (translation), it would fit exactly in Rectangle A.

Two geometric figures are called congruent if they have the same size and the same shape. Two congruent figures can be made to coincide exactly. Rectangle A is congruent to Rectangle B. In mathematical notation, this is written as A ≅ B.

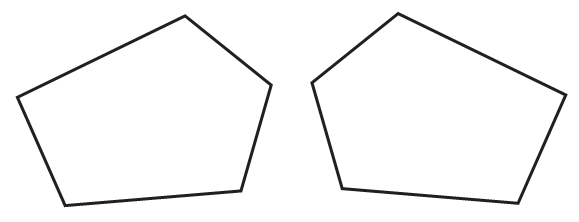

Look at the two polygons below. Are they congruent? Can one of the polygons be slid (translated), turned (rotated), and flipped (reflected) so that it can fit exactly over the other? The answer is yes, and therefore these two shapes are congruent. Their corresponding, or matching, angles are congruent and so are their corresponding sides.

Two are congruent if:

Line segments the measure of their lengths is the same

Circles they have congruent radii

Angles they have equal measure (degrees)

Polygons their corresponding parts (sides and angles)

are congruent

The congruence relationship ≅is reflexive (A ≅ A, because any figure is congruent to itself), symmetric (because A ≅ B means that B≅A), and transitive (because A ≅ B ≅F means that A ≅ F).

When an exact copy of a shape is made, the result is congruent shapes.

Sometimes, instead of making an exact copy, a scale model, or a drawing that is smaller or larger than the original, is made. Blueprints, copies of photos, miniatures, enlargements are all examples of a relationship that is somewhat different from congruence.

Look back at the figure that shows Rectangle A and Rectangle C. The sides of Rectangle A measure 1 unit by 2 units. The sides of Rectangle C measure 2 units by 4 units. The corresponding angles of the two rectangles are congruent. Rectangle A could be enlarged to look like Rectangle C, or C could be shrunk to look like A.

The mathematical term for shrinking or enlarging a figure is dilation. The sides of these two rectangles are proportional: 1:2= 2:4. When one figure can be made into another by dilation, the two figures are similar.

Two geometric figures are called similar if they have the same shape, so that their corresponding sides are proportional. Two similar figures may be of different sizes, but they always have the same shape.

Rectangle A is similar to Rectangle C. In mathematical notation, this is written as A ≈ C. Two congruent figures will always also be similar to each other, so A ≈B.

Look again at the rectangles. No matter how Rectangle D is dilated, translated, rotated, or reflected, it cannot be made to have the same shape as A or C. So D is neither congruent nor similar to any other rectangle in this figure.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

Konkle, Gail S. Shapes and Perception: An Intuitive Approach to Geometry. Boston: Prindle, Weber, & Schmidt, Inc., 1974.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة