Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Cross-linguistic patterns

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P181-C10

2026-01-15

6

Cross-linguistic patterns

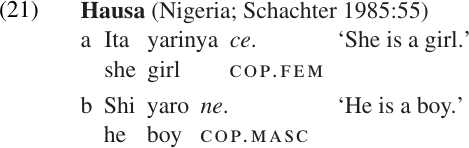

Up to now we have used the terms COPULA and LINKING VERB interchangeably. However, some languages have a copula which is not a verb. In Hausa, for example, verbs normally occur in the middle of a clause; the basic word order is S–Aux–V–O, with the auxiliary element indicating person, number, gender, and tense/aspect. The copula that appears in equative clauses, however, appears in final position and is inflected only for gender, as illustrated in (21). It does not fit well within either the category V or the category Aux.

In other languages, the copula may be an invariant particle: one that is never inflected but always appears in the same form, and only serves as the marker of a non-verbal clause type. Payne (1997:117) cites the Sùpyı̀re̒ language of Brazil as one such example.

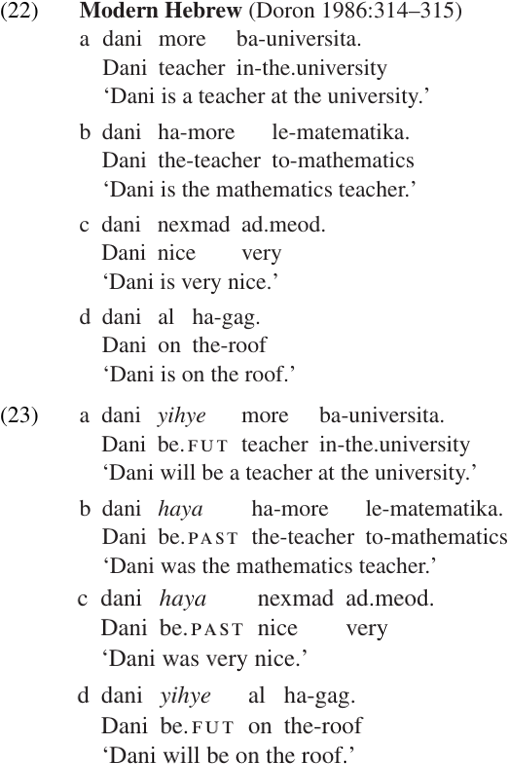

A number of languages have verbal copulae which are only used in non-present tenses. In Modern Hebrew, for example, attributive, equative, and locative clauses in the present tense do not contain any copula, as illustrated in (22), although they may optionally contain a nominative pronoun that doubles the subject NP (not shown here). In past or future tenses, however, an inflected copular verb (root: h.y.y) is obligatory, as illustrated in (23).

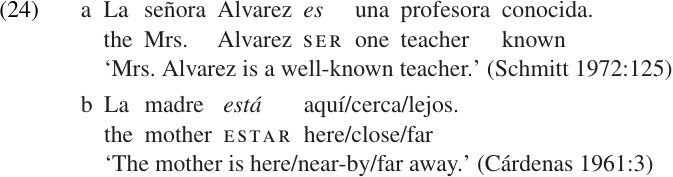

Spanish has two distinct copular verbs, ser and estar. The choice of which copula to use depends partly on the category of the predicate complement and partly on semantic factors. Ca̒rdenas (1961) states that ser is always used when the predicate complement is an NP, as in (24a), while estar is always used when the predicate complement is an adverbial element, as in (24b).

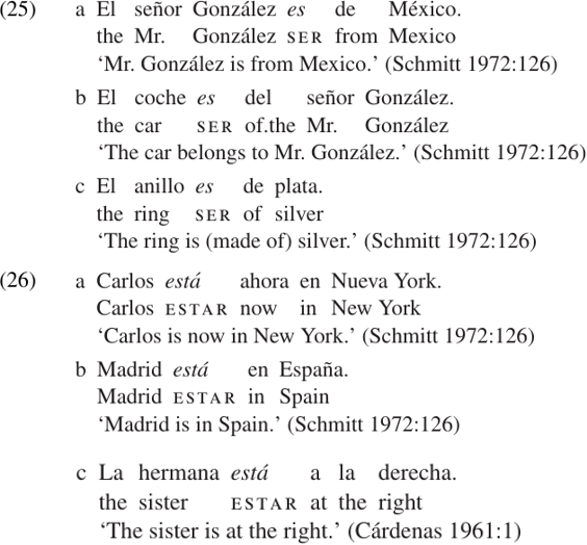

When the predicate complement is a prepositional phrase, ser is used with the preposition de ‘of, from’ in all its various senses; while estar is used with the prepositions en ‘in, on’ and a ‘at.’ Some examples are provided in (25–26).

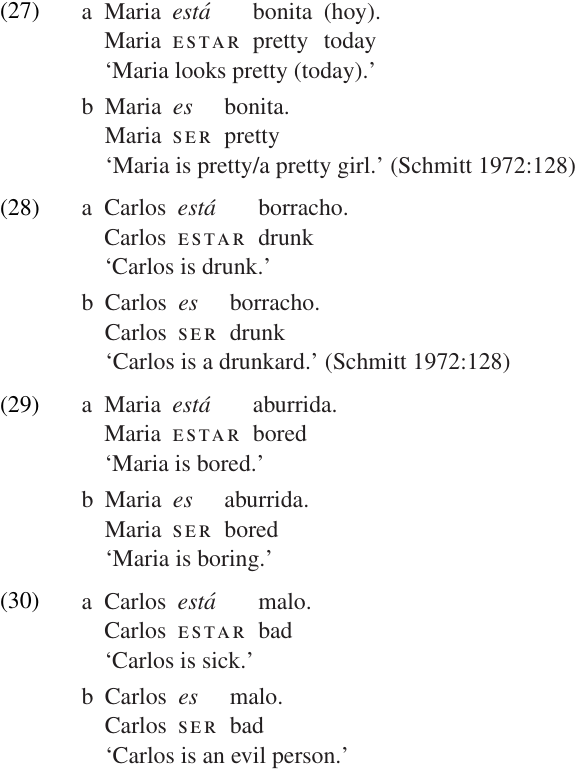

Notice that the choice of copula in locative clauses depends only on the specific preposition used; estar is used with the preposition en whether the location is understood as being temporary (26a) or permanent (26b). When the predicate complement is an adjective phrase, however, either copula may be used. The choice is made on semantic grounds: ser is used to express inherent properties or characteristics; while estar is used to express temporary states. This contrast is illustrated in (27–28). Some adjectives can take on two different meanings depending on which copula is used, as illustrated in (29–30).

We saw that the structure of a possessive construction may depend on the definiteness of the possessed item. This is not a special feature of Tagalog grammar, but is, in fact, a common pattern across languages: definiteness is often a major factor in determining the structure of a possessive clause. A Tagalog clause expressing ownership of a specific, definite item, like example (18b), is structurally very similar to a locative clause. Many other languages also exhibit strong similarities between definite possessive constructions and locative clauses (Clark 1978).

Tagalog clauses expressing possession or ownership of an indefinite or unspecified item, such as (18c), are structurally more similar to existential clauses. An important aspect of the similarity between indefinite possessives and indefinite existentials in many languages is that the same existential predicate is used for both constructions. It turns out that the predicate which is used for these two clause types in Tagalog is not used in stative, equative, or locative clauses. The same situation is found in Dusun, Land Dayak, and a large number of other Austronesian languages: there is a unique predicate for existentials and indefinite possessives, not used in other clause types. Outside of the Austronesian family, Clark (1978) notes the following languages where this same pattern is found: Amharic, Irish, Mandarin, Eskimo, French, Modern Greek, Hebrew, Twi, and possibly Arabic.

Of course, other patterns are also common. In Malay, the existential predicate is used for both possessive and locative clauses, and Clark reports the same pattern in Turkish and Yurok. English uses the copula be for existential and locative clauses, but have for possessives. Some languages use the same copula for all of these clause types.15

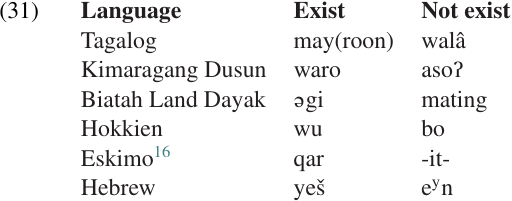

As noted above, Tagalog has two existential predicates: the positive may (or mayroon) and the negative walâ. The negative existential is different from the various negatives used in other contexts. Again, a number of other languages also have special negative existential forms. Some examples from various languages are shown in the following table:

15. Clark cites several examples from the Finno-Ugric (Finnish, Hungarian, and Estonian) and Indo-Iranian (Hindi, Kashmiri, and Bengali [past tense]) families.

16. The Eskimo and Hebrew examples are from Clark (1978:109).

الاكثر قراءة في Verbs

الاكثر قراءة في Verbs

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)