Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 8-3-2022

Date: 10-3-2022

Date: 2024-01-08

|

Adverbial collocations

One thing that is clear about manner adverbial modification of state verbs is that it is highly lexically restricted. The adverbs passionately and well, for example, combine with practically any agentive event predicate (eat lunch, make bread, play chess, and hundreds if not thousands more), but can only combine with a very few state predicates (hate, want, desire, and maybe a couple more for passionately and know for well). There is no such thing as knowing passionately, depending on passionately, or loving well. In some cases this selectivity might be semantically based (as is likely the case with passionately), but in other cases it is pure lexical selection.

Even in cases where the interpretation of the modifier is clearly some sort of degree modification, there is lexical selection. When we talk about a high degree of love, this is expressed as in (1a), whereas a high degree of knowledge is expressed as in (1b).

(1) a. He loves his son deeply/∗well.

b. He knows that well/∗deeply.

It appears that many manner adverb/state verb combinations exhibit a sort of conventionalized lexical relation, in other words they are collocations (Firth 1957). As with many other collocations, the particular meaning associated with an adverb–verb combination is not entirely predictable from their independent meanings. As we saw above, to know by face is something different than knowing. This selectivity and non-compositionality leads us to claim that many manner adverb/state verb combinations are, essentially, idiomatic, and not to be treated compositionally.

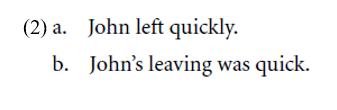

There are a number of issues that come up in connection with this claim. Chief among these is the apparent category-neutrality of the predicate modifier constructions. The parallel between verb–adverb and noun–adjective meanings evident in (2) has sometimes been raised as an argument for the Davidsonian analysis (Parsons 1990).

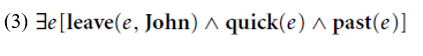

The basic idea is that the parallel between sentences such as (2a) and (2b) is captured by uniform Davidsonian semantic analysis such as that in (3).

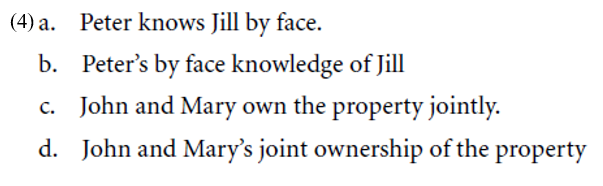

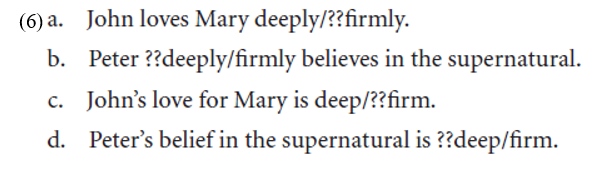

This argument has been extended to state verbs, with the parallels in (4) being taken as evidence for a neo-Davidsonian analysis.

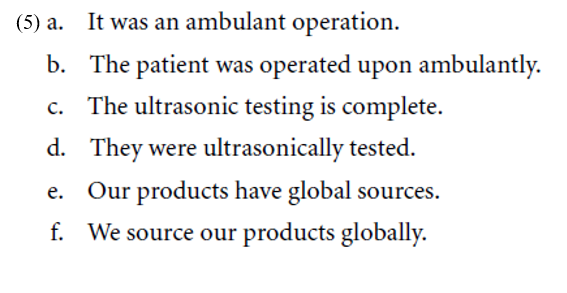

The parallel is, we suggest, a syntactic illusion. As has long been known, the collocational status of predicate-modifier structures is entirely independent of their actual syntactic category (Halliday 1966). This appears to be a quite general phenomenon, as illustrated by such examples as (5), where the semi idiomatic meaning of noun–adjective combinations are seen to carry over to their related verb–adverb use.

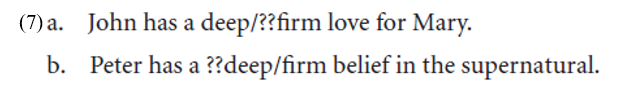

Likewise, nominalized state verbs evidence the same selectivity in their association with adjectives as the verb root itself shows with adverbial modification.1 Just as we cannot apply firmly to the verb love, or deeply to believe, we cannot apply firm to the noun love, or deep to belief (except in the sense of profound).

Associated adjective–noun combinations exhibit selectivity as well:2

Lexical selection, then, is category-neutral, and there appears to be a phenomenon (little studied) of root–root selection. Let us briefly explore what must be involved in providing a formal analysis of this. Rognvaldsson (1993) suggested treating such collocational elements as these as complex lexical items which are (optionally) inserted together into the derivation. This idea is directly related to much interesting work on the syntax of nominalization in the framework of Distributed Morphology (van Hout and Roeper 1997; Marantz 1997; London 2000), in which lexical items are taken to have a category-independent status.

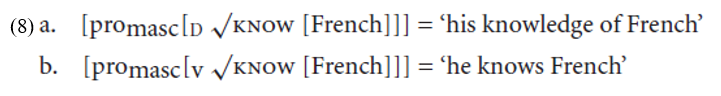

In essence the idea behind the Distributed Morphology analyses of nominalization is that there is no lexical difference between the roots kiss and love that appear as nouns and the roots kiss and love that appear as verbs. Marantz (2001) argues that nominalization is not a lexical process, but rather is the result of introducing a particular kind of root into a nominal environment. In other words, lexical items are introduced into the derivation in a category neutral way and acquire their syntactic features from their environment. This is illustrated schematically in (8).

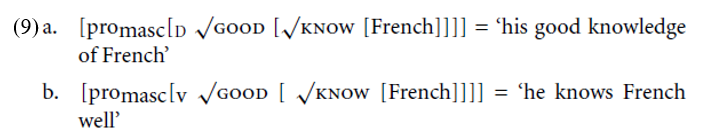

We can adopt a similar analysis of the apparent category-flexibility of modifiers

of these roots as well. There appears to be a modifier which appears with love and has the verbal-environment form “passionately” and a nominal environment form “passionate.” Let us assume that this is a single root passionate which also acquires its syntactic features (and thus its morphology) from its syntactic environment.

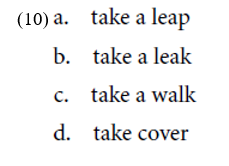

Marantz provides an account of verb–object idioms in a Distributed Morphology framework which is directly related. He suggests that the actual meaning of roots is listed not in a context-independent lexicon, but rather relative to the context of appearance and with respect to a locality domain. This allows us to account for the kind of light-verb lexical idioms given in (10), by essentially listing the different meanings.

Here presumably the root √take gets an appropriate meaning conditional on it occurring in the context of a particular direct object. Returning to our root-modifier case, then, the suggestion is that the root √know selects for a very particular meaning of the modifier √good, that is that √good has a context-dependent meaning listed once in the lexicon, namely its meaning when it occurs with √know, and that this shows up in all environments where these two roots appear together. Of course the modifier √good has a base manner reading, which is that that it has as an event verb modifier; it is just when it appears with √know that it acquires a specialized meaning. This is not dissimilar to the case of √take, which has a straightforward compositional meaning when combined with inanimate concrete object NPs such as the book, but an idiomatic reading in constructions of the take a leak type (Jackendoff 1996b).

Marantz argues that there are very fixed locality domains for this kind of conditional meaning – essentially the conditions need to be stated “within the vP.” One argument for this is that there are no idioms with a fixed agent piece, in the way we see the idioms in (10) have a fixed theme piece. Interestingly, as we noted in the introduction, it is exactly the class of manner adverbs that have this close syntactic association with the verb. In contrast to temporal and locative adverbs, manner adverbs are closely tied to the verb (McConnell-Ginet 1982; Cinque 1999). It might even be – and this is indeed pure syntactic speculation – that the syntactic difference between state verbs and event verbs interacts with this locality constraint. The structure we have assumed, is one on which the manner modifiers are vP (EventP-internal) but VP-external.

Assuming a strict syntax–semantics interface, this is the natural syntactic correlate of treating these modifiers as predicate modifiers, and it correlates with Marantz’s locality domain.

We have, then, at least the sketch of an account of the difference between manner modification of state verbs and manner modification of event verbs. In brief, manner modifiers cannot play their normal event-predicational role when they modify state verbs, so they must be reinterpreted. The tight syntactic binding between the verb and the adverb is why the typical Davidsonian entailment pattern doesn’t emerge – the adverbs are not acting as simple conjunctive predicates but as predicate modifiers. In the next two sections we discuss two kinds of predicate modifier meanings that these adverbs express.

1 Of course even standard idiomatic expressions evidence this category neutrality:

(i) a. The pulling of strings that they engaged in brought about their downfall.

b. His kicking the bucket caused an uproar.

2 Greenbaum (1982) has pointed out that in some cases there are missing elements in the paradigm. The degree reading of the adverbs well and badly in collocation with the verbs know and need doesn’t appear to extend to the adjectives good and bad in collocation with the nominalized forms of these verbs:

(i) a. Peter knows Mary intimately/well.

b. Peter’s knowledge of Mary is intimate/∗good.

(ii) a. Peter needs a haircut desperately/badly.

b. Peter’s need for a haircut is desperate/∗bad.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: حفنة من الجوز يوميا تحميك من سرطان القولون

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تنشيط أول مفاعل ملح منصهر يستعمل الثوريوم في العالم.. سباق "الأرنب والسلحفاة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي يقيم دورة تطويرية عن أساليب التدريس ويختتم أخرى تخص أحكام التلاوة

|

|

|