Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-09-13

Date: 2024-09-27

Date: 2024-10-01

|

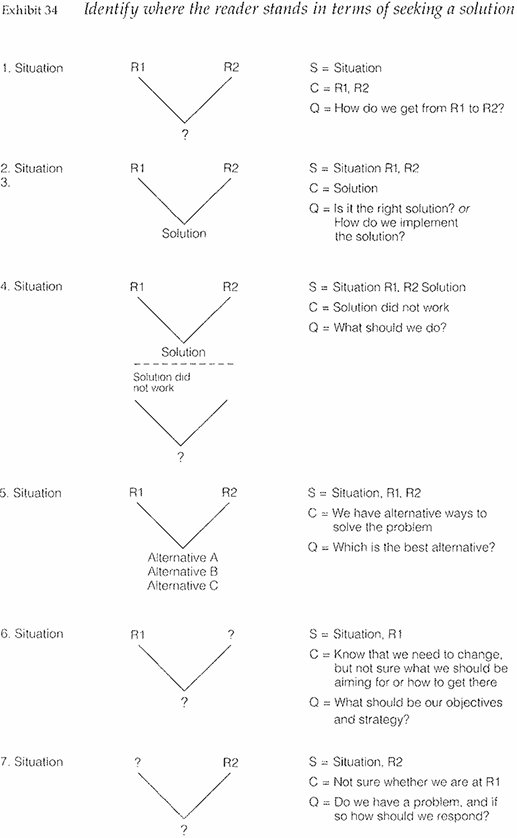

Once you have the basic parts of the problem laid out, you are ready to look for the reader's question. This question will depend on how far along in the problem the reader has progressed before you began to analyze it. Does he simply want to know how to get from R1 to R2? Or has he already decided how to do that, in which case he will of course have a different question.

A big error some writers make is in not specifying to themselves whether some action has already been taken by the reader to solve the problem. Recognizing when action has been taken-and how that affects the question a document is meant to answer-greatly simplifies writing the introduction and structuring the subsequent reasoning.

Using the problem definition as a guide, we can see that readers will generally face one of seven problem situations, depending on where they stand in terms of seeking a solution:

Most common circumstances

1. They do not know how to get from R1 to R2.

2. They think they know how to get from R1 to R2, but they are not certain they are right.

3. They know for sure how to get from R1 to R2, but they do not know how to implement the solution.

Variations on the most common circumstances

4. They thought they knew how to get from R1 to R2 and implemented it, but that solution turned out not to work for some reason.

5. They have identified several possible solutions, but don't know which to pick.

Also possible but not common

6. They know R1 but cannot articulate R2 specifically enough to permit looking for a solution.

7. They know R2 but are not sure whether they are at R1 (typical benchmarking study).

Exhibit 34 shows how the elements of the problem definition would map to the introduction in each of the seven cases.

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

شعبة فاطمة بنت أسد (عليها السلام) تنظم دورة تخصصية في أحكام التلاوة

|

|

|