Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Personal pronouns: agreement features

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P138-C8

2026-01-02

22

Personal pronouns: agreement features

Agreement between a pronoun and its antecedent helps the listener to interpret the pronoun correctly. In English a pronoun must agree with its antecedent for person, number, and gender. This requirement prevents the pronoun she in sentence (14) from finding an antecedent within its sentence, since there is no feminine NP available. The antecedent must come from the discourse context, or from the speech situation.

(14) John told Bill that she had won the election.

All languages appear to have some kind of pronoun agreement. We noted that person, number, and gender are the most commonly marked categories in pronoun systems, as in verb agreement systems. Of these, person and number appear to be marked in all languages. Joseph Greenberg (1963), in his pioneering study of language universals, stated:

“All languages have pronominal categories involving at least three persons and two numbers.”

(Universal 42)

So, all languages distinguish first, second, and third person pronouns, although in some languages third person pronouns have the same form as articles or demonstratives. Beyond these three basic categories, the most common further distinction is a contrast in the first-person plural between INCLUSIVE and EXCLUSIVE forms. A first-person inclusive pronoun (e.g. Malay kita) refers to a group which includes both the speaker and the hearer (‘you, me, and [perhaps] those others’). A first-person exclusive pronoun (e.g. Malay kami) refers to a group which includes the speaker but excludes the hearer (‘me and those others but not you’).

In the years since Greenberg published his study a few languages have been found in which pronouns are not specified for number.1 Most languages, however, do make a distinction between singular and plural pro nouns, at least in the first person (I vs. we). Modern English has lost its number distinction in the second person, and many languages have no number distinction in the third person. In addition to the basic contrast between singular and plural, many languages have a DUAL category for groups containing exactly two individuals. Dual number is found most commonly in first person forms. Any language that has a distinct dual form in the third person will almost certainly have distinct dual forms for the first and/or second persons as well.2

A few languages have a further distinct number category, TRIAL (for groups of three) or PAUCAL (for groups containing a few individuals).3 Even in languages which have a trial number category, it is fairly common for the trial forms to be used at times in an extended, paucal sense to refer to more than three individuals.

The Susurunga language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have a complete set of quadral pronouns, which contrast with singular, dual, trial, and plural forms in all four persons (first inclusive, first exclusive, second, third).4 The dual, trial, and quadral forms each contain incorporated numeral morphemes (‘two,’ ‘three,’ ‘four,’ respectively). However, the quadral forms actually have the meaning ‘four or more,’ rather than ‘exactly four.’ They are primarily used in two specific contexts: first, with relationship terms, as in ‘we (four or more) who are in a mother–child relationship,’ where plural forms are not allowed; and second, in hortatory discourse (speeches of exhortation), where speakers make frequent use of first person inclusive quadral forms to maintain a sense of identity with the listeners.

In addition to person and number, many languages have distinct pronoun forms to indicate the gender or noun class of the antecedent. Gender is most commonly marked in third person forms, and is never distinguished in the first person unless it is also distinguished in the second and/or third person.5

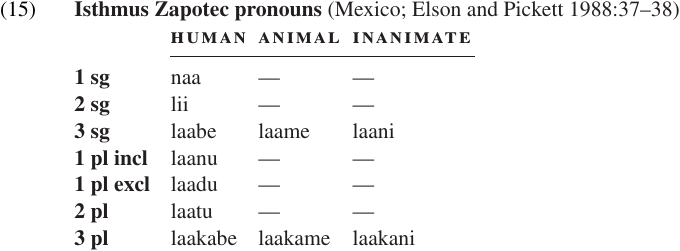

As mentioned in Noun classes and gender, European languages tend to distinguish two genders (masculine and feminine, as in Portuguese) or three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter, as in German). Another common gender classification is human vs. animal vs. inanimate, as found in Isthmus Zapotec. Note that gender is distinguished only in the third person forms:

There is one important category which is not relevant to verb agreement systems but is often marked on pronouns because of the fact that pronouns function as noun phrases, and that is case. In languages where all NPs are marked for case, it is not uncommon for pronouns to have special inflected forms, rather than taking the normal set of case markers. Even where other NPs are not marked for case, pronouns may be inflected for case. This is the situation in English (I, me, my; we, us, our; he, him, his; etc.). And, as we saw, the case-marking pattern for pronouns may be accusative even when the case marking pattern for other NPs is ergative.

Some languages have distinct third person pronoun forms which indicate degree of PROXIMITY, i.e. how far the third person is from the speaker and hearer. Often this involves a distinction between someone who is visible to the speaker and hearer vs. someone who is invisible.

Finally, the choice of pronoun is often used to signal politeness. It is quite common for languages to have two different second person singular forms, one formal and the other informal or familiar (e.g. German du vs. Sie; French tu vs. vous; Biatah Land Dayak ku’u vs. ka’am). More complex systems are common in southeast Asia. Malay speakers must choose among half a dozen or more possible forms for both the first- and second-person singular category, depending on the relative social status and degree of intimacy between the speaker and hearer. Often speakers will use kinship terms or proper names for both first- and second-person reference, to avoid having to make this potentially embarrassing choice.

1. Foley (1986:70–71) mentions several Papuan languages from the island of New Guinea which do not have distinct singular vs. plural pronoun forms. Asheninca Campa (Peru) may be another counter-example to Greenberg’s generalization. Reed and Payne (1986) report that Asheninca pronouns can optionally be pluralized using the same plural suffix used for nouns, but in fact this is rarely done where the number can be inferred from the context.

2. Again, there are parallels between pronouns and agreement systems. An interesting fact about the very complex Southern Tiwa agreement pattern, discussed in Case and agreement, is that dual number is marked in subject agreement but not in direct or indirect object agreement, which distinguish only singular vs. plural.

3. Greenberg’s Universal 34 states: “No language has a trial number unless it has a dual. No language has a dual unless it has a plural.”

4. Hutchisson (1986).

5. Greenberg’s Universal 44. Moreover, there are many languages in which gender is distinguished only in singular forms, but there appears to be no language in which gender is distinguished only in plural forms (Universal 37).

الاكثر قراءة في Personal pronoun

الاكثر قراءة في Personal pronoun

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)