Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Uninterpretable features and feature-deletion

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

287-8

28-1-2023

2594

Uninterpretable features and feature-deletion

Our discussion of how case and agreement work in a sentence such as (5B) has wider implications. One of these is that items may enter the derivation with some of their features already valued and others as yet unvalued: e.g. BE enters the derivation in (6) with its tense feature valued, but its  -features unvalued; and THEY enters with its

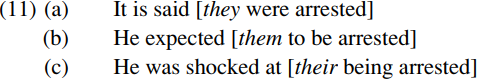

-features unvalued; and THEY enters with its  -features valued but its case feature unvalued. This raises the question of which features are initially valued when they first enter the derivation, which are initially unvalued – and why. Chomsky (1998) argues that the difference between valued and unvalued grammatical features correlates with a further distinction between those grammatical features which are interpretable (in the sense that they play a role in semantic interpretation), and those which are uninterpretable (and hence play no role in semantic interpretation). For example, it seems clear that the case feature of a pronoun like THEY is uninterpretable, since a subject pronoun surfaces as nominative, accusative or genitive depending on the type of [bracketed] clause it is in, without any effect on meaning – as the examples in (11) below illustrate:

-features valued but its case feature unvalued. This raises the question of which features are initially valued when they first enter the derivation, which are initially unvalued – and why. Chomsky (1998) argues that the difference between valued and unvalued grammatical features correlates with a further distinction between those grammatical features which are interpretable (in the sense that they play a role in semantic interpretation), and those which are uninterpretable (and hence play no role in semantic interpretation). For example, it seems clear that the case feature of a pronoun like THEY is uninterpretable, since a subject pronoun surfaces as nominative, accusative or genitive depending on the type of [bracketed] clause it is in, without any effect on meaning – as the examples in (11) below illustrate:

By contrast, the (person/number)  -features of pronouns are interpretable, since e.g. a first-person-singular pronoun like I clearly differs in meaning from a third-person-plural pronoun like they. In the case of finite auxiliaries, it is clear that their tense features are interpretable, since a present-tense form like is differs in meaning from a past-tense form like was. By contrast, the (person/number)

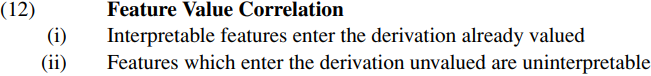

-features of pronouns are interpretable, since e.g. a first-person-singular pronoun like I clearly differs in meaning from a third-person-plural pronoun like they. In the case of finite auxiliaries, it is clear that their tense features are interpretable, since a present-tense form like is differs in meaning from a past-tense form like was. By contrast, the (person/number)  -features of auxiliaries are uninterpretable, in that they serve purely to mark agreement with a particular nominal. This suggests a correlation such as (12) below between whether or not features are interpretable and whether or not they are initially valued:

-features of auxiliaries are uninterpretable, in that they serve purely to mark agreement with a particular nominal. This suggests a correlation such as (12) below between whether or not features are interpretable and whether or not they are initially valued:

The correlation between valuedness and interpretability turns out to be an important one. (It should be noted that Chomsky 1998 offers a rather different formulation of (12ii) to the effect that uninterpretable features enter the derivation unvalued, but his claim seems problematic e.g. for languages in which nouns may enter the derivation with an uninterpretable gender  -feature with a fixed but arbitrary value: e.g. the noun M¨adchen ‘girl’ is inherently neuter in gender in German, though it denotes a feminine entity.)

-feature with a fixed but arbitrary value: e.g. the noun M¨adchen ‘girl’ is inherently neuter in gender in German, though it denotes a feminine entity.)

As we saw in the simplified model of grammar which we have presented, each structure generated by the syntactic component of the grammar is subsequently sent to the PF component of the grammar to be spelled out (i.e. assigned a PF representation which provides a representation of its Phonetic Form). If we assume that unvalued features are illegible to (and hence cannot be processed by) the PF component, it follows that every unvalued feature in a derivation must be valued in the course of the derivation, or else the derivation will crash (i.e. fail) because the PF component is unable to spell out unvalued features. In more concrete terms, this amounts to saying that unless the syntax specifies whether we require e.g. a first-person-singular or third-person-plural present-tense form of be, the derivation will crash because the PF component cannot determine whether to spell out BE as am or are.

In addition to being sent to the PF component, each structure generated by the syntactic component of the grammar is simultaneously sent to the semantic component, where it is converted into an appropriate semantic representation. Clearly, interpretable features play an important role in the computation of semantic representations. Equally clearly, however, uninterpretable features play no role whatever in this process: indeed, since they are illegible to the semantic component, we need to devise some way of ensuring that uninterpretable features do not input into the semantic component. How can we do this?

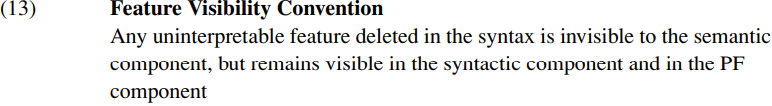

Chomsky’s answer is to suppose that uninterpretable features are deleted in the course of the syntactic derivation, in the specific sense that they are marked as being invisible in the semantic component while remaining visible in the syntax and in the PF component. To get a clearer idea of what this means in concrete terms, consider the uninterpretable nominative case feature on they in (5B) They were arrested. Since this case feature is uninterpretable, it has to be deleted in the course of the syntactic derivation, so that the semantic component cannot ‘see’ it. However, the PF component must still be able to ‘see’ this case feature, since it needs to know what case has been assigned to the pronoun THEY in order to determine whether the pronoun should be spelled out as they, them or their. This suggests the following convention:

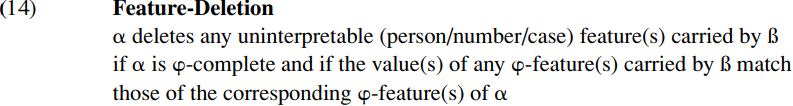

The next question to ask at this juncture is what kind of syntactic operation is involved in the deletion of uninterpretable features. Let’s suppose (following Chomsky) that feature-deletion involves the kind of operation outlined informally below (where  and ß enter into an agreement relation, and one is a probe and the other a goal):

and ß enter into an agreement relation, and one is a probe and the other a goal):

Here,  and ß are two different constituents contained within the same structure, and one is a probe and the other a goal. In a language like English where finite verbs agree with their subjects in person and number (but not gender), ß is

and ß are two different constituents contained within the same structure, and one is a probe and the other a goal. In a language like English where finite verbs agree with their subjects in person and number (but not gender), ß is  - complete if it carries both person and number features (though in a language like Arabic where finite verbs agree in person, number and gender with their subjects, ß is

- complete if it carries both person and number features (though in a language like Arabic where finite verbs agree in person, number and gender with their subjects, ß is  -complete if it carries person, number and gender: see Nasu 2001, 2002 for discussion). For ß to delete the person/number/case features of

-complete if it carries person, number and gender: see Nasu 2001, 2002 for discussion). For ß to delete the person/number/case features of  , the

, the  -features of ß must match the

-features of ß must match the  -features carried by

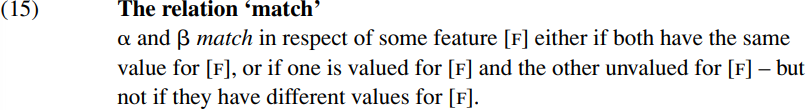

-features carried by  . Let’s define the relation ‘match’ in the following terms:

. Let’s define the relation ‘match’ in the following terms:

To make a rather abstract discussion more concrete, let’s consider how feature-deletion applies in the case of our earlier structure (10) above. Here, both BE and THEY are  -complete, since both are specified for person as well as number. Moreover, the two match in respect of their

-complete, since both are specified for person as well as number. Moreover, the two match in respect of their  -features, since the two have the same value for person and number (in that both are third person plural). Let’s assume that (in consequence of the Earliness Principle), feature-deletion applies as early as possible in the derivation, and hence applies at the point where the structure in (10) has been formed. In accordance with Feature-Deletion (14),

-features, since the two have the same value for person and number (in that both are third person plural). Let’s assume that (in consequence of the Earliness Principle), feature-deletion applies as early as possible in the derivation, and hence applies at the point where the structure in (10) has been formed. In accordance with Feature-Deletion (14),  -complete BE can delete the uninterpretable case feature carried by THEY; and conversely

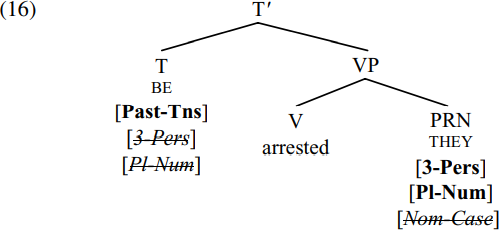

-complete BE can delete the uninterpretable case feature carried by THEY; and conversely  -complete THEY can delete the uninterpretable person/number features carried by BE. Feature-Deletion therefore results in the structure (16) below (where

-complete THEY can delete the uninterpretable person/number features carried by BE. Feature-Deletion therefore results in the structure (16) below (where strikethrough indicates deletion):

The deleted features will now be invisible in the semantic component – in accordance with (13). The rest of the derivation proceeds as before.

Chomsky sees uninterpretable features as being at the very heart of agreement, and posits (1999, p. 4) that ‘Probe and Goal must both be active for Agree to apply’ and that a constituent  (whether Probe or Goal) is active only if

(whether Probe or Goal) is active only if  contains one or more uninterpretable features. In other words, it is the presence of uninterpretable features on a constituent that makes it active (and hence able to serve as a probe or goal, and to play a part in feature-valuation and feature-deletion).

contains one or more uninterpretable features. In other words, it is the presence of uninterpretable features on a constituent that makes it active (and hence able to serve as a probe or goal, and to play a part in feature-valuation and feature-deletion).

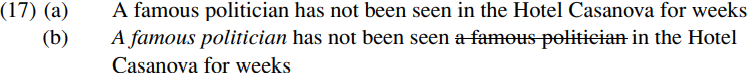

As should be obvious, the Feature-Deletion operation posited in (14) is very different from the (Trace) Copy-Deletion operation we assumed by which a trace copy of a moved constituent is deleted. Feature-Deletion is an operation which renders the affected features invisible to the semantic component, while leaving them visible to the phonological component. By contrast, Copy-Deletion is an operation which renders traces of moved constituents invisible to the phonological component (in the sense that they are not given any phonetic spellout), while leaving them visible in the semantic component. The reason why traces must remain visible in the semantic component is that they play an important role in semantic interpretation, as we can see in relation to a sentence such as (17a) below, which has the simplified structure (17b) (assuming that a famous politician originates as the object of the passive participle seen and raises to become the subject of has):

(17a) exhibits a scope ambiguity in respect of whether a famous politician has scope over not (so that the sentence is paraphraseable as ‘There is a specific famous politician, Gerry Attrick, who has not been seen in the Hotel Casanova for weeks’) or conversely whether not has scope over a famous politician (so that the sentence is paraphraseable as ‘Not a single famous politician has been seen in the Hotel Casanova for weeks’). If the semantic component is able to ‘see’ traces, it will ‘see’ the structure represented in skeletal form in (17b) above. One way of handling the scope ambiguity of sentences like (17a) is to posit that scope is defined in terms of c-command and that the scope ambiguity correlates with the fact that in the structure (17b), not is c-commanded by (so falls within the scope of) the moved constituent a famous politician, but conversely not c-commands (and hence has scope over) its trace a famous politician. A plausible conclusion to draw is that trace-deletion takes place in the phonological component, so that traces remain in the syntax and hence are visible in the semantic component, and can play a role in determining scope in relevant types of structure. The assumption that trace-deletion is a phonological operation is implicit in Chomsky’s remark (1999, p. 11) that ‘Phonological rules... eliminate trace.’

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)