Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

أقرأ أيضاً

التاريخ: 2024-01-11

التاريخ: 10-1-2022

التاريخ: 2024-01-23

التاريخ: 2024-01-15

|

Building an alternative: An analogy to definite descriptions

An essential problem here is this: It seems to be a fundamental property of expressive meaning (or conventional implicatures) that a constituent with such an interpretation can’t contain a variable inside it that is bound from outside it. (Karttunen and Peters 1975 termed this the “binding problem.”) The way around this is to suppose that nonrestrictive modification always involves reference, or at least some form of quantificational independence. The problem faced here is that in, for example, unsuitable word or damn Republican, the modified expression is property-denoting. So how then to reconcile this with the need to keep expressive and at-issue meaning apart from each other in the right way? What do expressive modifiers modify?

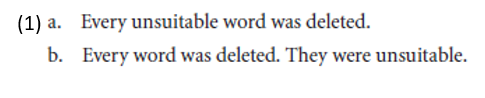

To address this question, it may help to momentarily revisit an old analytical intuition: that expressive meaning (or in any case nonrestrictive modification) involves, in some sense, interleaving two utterances, one commenting on or elaborating the other. Seen in this light, perhaps the Larson and Marušiˇc (2004) paraphrase of (1a) in (1b) is not only apt, but also revealing:

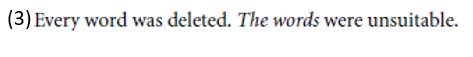

What’s special about (1a) (on the relevant reading) is that it is a way of saying both sentences of (1b) at once. And the linguistic trick that makes (35b) possible is using they to refer back to a plural individual consisting of the set quantified over by every.

Thus an answer to the question just raised presents itself: Maybe what these nonrestrictive modifiers modify is a potentially plural discourse referent such as the one the pronoun in (1b) refers to.

Importantly, the anaphora (1b) would not be possible with a singular pronoun:

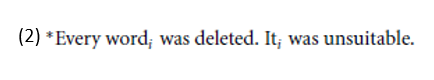

That is, 2) can’t mean “Every word was deleted and unsuitable.” A natural assumption about why this anaphora is nonetheless possible in (1b) is that this they is an E-type pronoun, and consequently is interpreted like a definite description (Heim 1990):

This approach helps avoid an interpretation that includes an element such as “words were unsuitable,” because, unlike kinds, definite descriptions involve a contextual domain restriction.

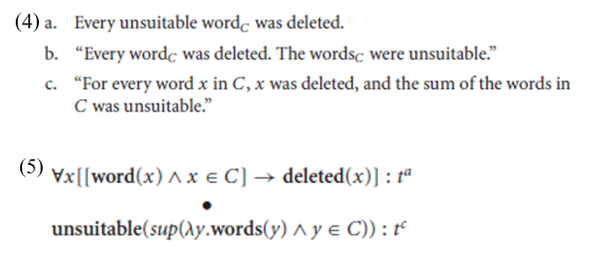

What’s being quantified over in the unsuitable-words example is not, of course, all words, but only the contextually relevant ones – a fact I’ll reflect here using a contextually supplied resource domain variable C (Westerstahl 1985; von Fintel 1994), as in (4) and (5).1

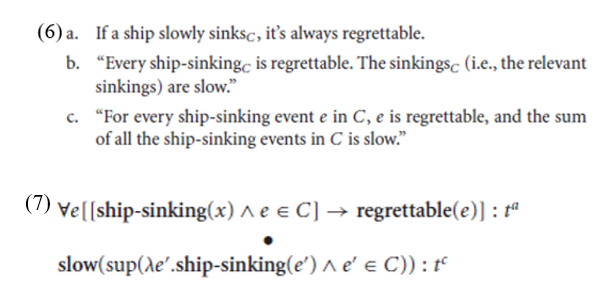

Roughly analogous assumptions are possible for adverbs:

Striving to assemble these interpretations may be a step toward a more adequate general understanding.

It also provides an alternative way of understanding the damn facts in the previous sections. On this view, the damn machine will convey disapproval of only the machine relevant in the context, and the fucking people next door, disapproval of contextually relevant people next door.

1 In addition to contextual domain restrictions, these rough interpretations introduce a supremum operator that loosely corresponds to the definite determiner in the paraphrases. This is not as significant a move, however. Indeed, the Chierchia (1984) nominalizing type-shift ∩ itself has this general kind of semantics (at least extensionally). Note also that I am placing the resource variable C directly in the syntax, as a subscript on the head.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|