Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-06-15

Date: 2024-05-06

Date: 2024-03-30

|

English Consonants Stops

We will start our account of the English consonants and their allophones with the most versatile group, stops. Articulation of stops can be analyzed in three stages (closing stage, closed stage, and release stage).

English has six stop phonemes, /p, b, t, d, k, g/. Their differences can be examined in different dimensions. Firstly, with respect to place of articulation, there is a three-way distinction: bilabials /p, b/, alveolars /t, d/, and velars /k, g/. Bilabials /p/ and /b/ are made by forming the closure with upper and lower lips and, after building up the pressure necessary, releasing the closure abruptly, as in pay [pe] and bay [be]. Alveolar stops /t/ and /d/ utilize the tip of the tongue to form the closure with the alveolar ridge, as in tip [tɪp] and dip [dɪp]. Finally, for velars /k/ and /g/, we raise the back of the tongue to make a contact with the soft palate (velum), as in cap [kæp] and gap [gæp].

While the account of the places of articulation for stops is very straightforward, the characteristics related to their voicing are not so. It is customary to see labels such as ‘voiceless’ and ‘voiced’ for /p, t, k/ and /b, d, g/, respectively, in several manuals. Although this definitely reflects the truth for /p, t, k/, which are always voiceless, and may indeed be true for /b, d, g/ of several languages (e.g. Spanish, French, etc.), it will hold in English only for the intervocalic position in such words as aboard [əbɔɹ̣d], adore [əbɔɹ̣], eager [igɚ]. In initial and final positions (following or preceding silence) /b, d, g/ are partially voiced, if at all.

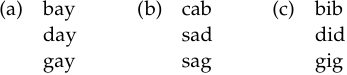

In the words in (a), we may have partially voiced (and indeed little voiced, i.e. with very little vocal cord activity) /b, d, g/ in initial positions. In (b), the words contain partially voiced final stops. In (c), each word has /b, d, g/ in both initial and final positions that are not fully voiced. Because English /b, d, g/ are fully voiced only in intervocalic position, several phoneticians prefer the classification in terms of fortis and lenis to differentiate /p, t, k/ from /b, d, g/. Accordingly, fortis stops /p, t, k/ are pronounced with more muscular energy (force), higher intra-oral pressure, and a stronger breath effort than their lenis counterparts /b, d, g/. Following the popular usage, we will employ the labels ‘voiced’ and ‘voiceless’, but the reader should remember the more accurate lenis vs. fortis distinction in initial and final positions.

Before we leave the discussion of initial and final devoicing, some clarifications are needed. Firstly, it should be stated that devoicing in these positions is not total, and does not make these stops indistinct from their voiceless counterparts. Thus, partially devoiced [b̥, d̥, g̥] are not [p, t, k], respectively. Secondly, there is almost always a difference in the degree of voicing; final devoicing is greater than initial devoicing. Thus, in the (c) words above, [b̥ɪb̥], [d̥ɪd̥], [g̥ɪg̥], the final stops normally have greater devoicing than their initial counterparts. Finally, it should be pointed out that final devoicing is present if there is no voiced sound coming immediately after; if there is a voiced sound immediately after, devoicing does not take place. For example, while the final sound of dog is partially devoiced, the same is not observed in dog meal, because in the latter, /g/ is immediately followed by a voiced sound, /m/ (cf. dog-food).

When a stop is preceded by a /s/, the distinction between /p, t, k/ and /b, d, g/ is not in voicing, but lies in fortis/lenis. For example, the velar stops /k/ and /g/ are not in any way different in voicing in the following pairs of words: discussed– disgust, misspell– Miss Bell, disperse– disburse. The difference lies in fortis and lenis productions respectively.

The type of stop (/p, t, k/ or /b, d, g/) influences the length of the pre ceding vowel in that vowels are longer before voiced (lenis) stops than before voiceless (fortis) stops. This difference seems to be much more noticeable when the syllable contains a long vowel or a diphthong. Pairs such as lobe– slope, vibe– wipe (/b/ – /p/), wide– white, ride– right (/d/ – /t/), league– seek, league– leak (/g/ – /k/) illustrate the difference in the length, whereby the first member of each pair has the longer vowel because it is fol lowed by a voiced stop. The influence on the length of the preceding segments is not restricted to vowels and diphthongs, but can also be observed with nasals and laterals. If we compare the following pairs, killed– kilt, send– sent, amber– ampere, we see that the sonorants in the first member of each pair are longer.

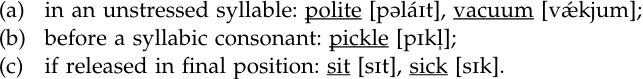

Another dimension that differentiates /p, t, k/ from /b, d, g/ in English is the feature of aspiration. The voiceless set of stops is pronounced with aspiration at the beginning of stressed syllables (pay [phe], take [thek], cab [khæb]). That this characteristic is not restricted to word-initial position can be verified in words such as apart [əphaɹ̣t], attack [əthæk], occur [əkhɝ], where the aspirated stops are not word-initial, but in initial positions of stressed syllables. In American English (AE), this is the most common pattern. In addition, voiceless stops may be produced with weak aspiration in the following positions:

In their release stage, syllable-final (especially word-final) single coda stops are often produced with no audible release. The following examples illustrate the point with the appropriate diacritic for unreleased stops: mop [mɔp⸣], sit [sɪt⸣], sack [sæk⸣], mob [mab⸣], sad [sæd⸣], bag [bæg⸣]. When it is not following a vowel, most speakers release the final /t/ (e.g. fast).

When we have a word with two non-homorganic (i.e. not from the same place of articulation) stops in a row, there is no audible release for the first stop; the closure of the second stop in sequence is made before the release of the first stop.

sipped [sɪp⸣t] /p + t/ cheap date [tʃip⸣det] /p + d/ sobbed [sɑb⸣d] /b + d/

When we have two homorganic (i.e. sharing the same place of articulation) stops in a sequence, there is no separate release for the first stop; rather, there is one prolonged closure for the two stops in question. This is valid for cases where there is voicing agreement, as in big girl, black cat, sad dog, stop please, as well as sequences with different voicing, as in top block, white dog, black girl.

An assimilatory situation arises when a non-alveolar stop is preceded by an alveolar stop, as in night cap [naɪt kæp] → [naɪk:æp], white paper [waɪt pepɚ] →[waɪp:epɚ], red badge [ɹ̣εd bæʤ] → [ɹ̣εb:æʤ], weed killer [wid kɪlɚ] → [wigkɪlɚ]. As we see in these examples, alveolar stops /t, d/ become bilabial [p, b] or velar [k, g] respectively, because of the following bilabial/velar stops, while maintaining the original voicing.

The stop closure is maintained and nasally released in cases in which the stop is followed by a homorganic nasal. In this process, which is known as ‘nasal plosion’, the air is released through the nasal cavity. This happens in the following environments:

(a) The nasal is syllabic: button [bΛtn̩] /t + n/, sudden [sΛdn̩] /d + n/, taken [tekŋ̩] /k + ŋ/.

(b) The nasal is in the initial position of the following syllable of the word: submarine [sΛbməɹ̣in] /b + m/, madness [mædnəs] /d + n/.

(c) The nasal is in the initial position of the next word: hard nails [hɑɹ̣dnelz] /d + n/, sad news [sædnuz] /d + n/.

A comparable release, this time laterally, is provided when the stop is followed by a homorganic lateral. This process, which is known as ‘lateral plosion’, can be observed in the following words: cattle [kætl̩] /t + l/, middle [mɪdl̩] /d + l/, as well as in sequences of words, bud light [bΛdlaɪt] /d + l/, at last [ətlæst] /t + l/. That this event requires homorganicity is further shown by examples such as tickle [tɪkl̩] or nipple [nɪpl̩], which have no lateral release.

Putting all this information together, we can say that the following parameters need to be looked at in differentiating the stops /p, t, k/ from /b, d, g/. In initial position, fortis vs. lenis and/or aspirated vs. unaspirated should be considered. Medial position is the only one in which voicing is a distinguishing factor; in addition, length of the preceding sound (longer vowels and sonorants before /b, d, g/) and aspiration if the stop is at the initial position of a stressed syllable should be considered. In final position, the length of the preceding sound would be the most crucial aspect.

Apart from these general patterns exhibited, certain stops have characteristics of their own. Alveolar stops are realized as dental when they occur immediately before interdentals, as illustrated in the following: bad [bæd] bad things [bæd̪θɪŋz]; great [gɹ̣et] – great things [gɹ̣et̪θɪŋz].

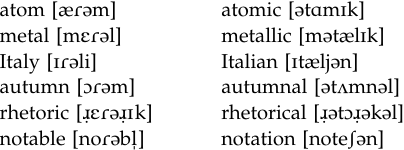

For many speakers of American English, words such as letter, atom, header, and ladder are pronounced as [lεɾɚ], [æɾəm], [hεɾɚ], [læɾɚ], respectively. This process, which is known as flapping (tapping in some books, which is a more correct characterization), converts an alveolar stop to a voiced flap/tap. The most conducive environment for this process is intervocalic, when the second syllable is not stressed. Thus, while attic [ǽɾɪk] has a flap, attack [əthǽk] does not because, in the latter, the alveolar stop is the onset of a stressed syllable. This pattern is also revealed in morphologically related but prosodically different word pairs. Thus, while the /t/ targets in the left column below (in unstressed syllables) undergo this process, they do not do so in the morphologically related words in the right column (in stressed syllables).

The principle is also valid across word boundaries; for example, we get at all [ǝɾɔl] (flapped because /t/ is the coda of the unstressed syllable) but a tall [ǝ tɔl] (not flapped because /t/ is the onset of the stressed syllable). Similarly, the /t/ target in eat up [iɾΛp] is flapped, but in e-top [i tap] it is not. Although in a great majority of cases of flapping (all the above included) the first vowel is stressed, this is not a necessary condition. For example, in words such as nationality [næʃənǽləɾi], sorority [səɹ̣ɔ́ɹ̣əɾi], calamity [kəlǽməɾi], flapping occurs between two unstressed vowels. Thus, the only condition related to stress is that the target alveolar stop cannot be in a stressed syllable. (This condition also includes the secondary stress; thus, we don't have flapping in words such as sanitary, sabotage, latex, etc., in which /t/ targets are in syllables with secondary stress) Besides the clear inter- vocalic environments that were given above, there are two other environments that seem to provide the context for this process. These are (a) the r-coloring of the first vowel, as exemplified in porter [pɔɹ̣ɾɚ], border [bɔɹ̣ɾɚ], and (b) the following syllabic liquid, as in little [lɪɾl̩], cattle [kæɾl̩], bitter [bɪɾɚ], and butter [bΛɾɚ].

Before finishing the discussion of flapping, mention should be made of the cases of homophony created by the neutralization of the distinction between the alveolar stops, as illustrated by the pairs writer– rider [ɹ̣aɪɾɚ], grater– grader [gɹ̣eɾɚ], latter– ladder [læɾɚ], bitter– bidder [bɪɾɚ], liter– leader [liɾɚ]. While many speakers of American English pronounce such pairs homophonously, there are others who make a distinction between these words. However, whenever the distinction is made, it is related not to the pronunciation of the alveolar stop, but to the preceding vowel/diphthong. Following the generalization, we looked at earlier, where it was stated that vowels/diphthongs were longer before voiced than before voiceless stops, we could predict that /aɪ/ and /e/ would be longer in rider and grader than in writer and grater respectively. Similarly, the vowels /æ/ and /ɪ/ would be longer in ladder and bidder than in latter and bitter. The phenomenon described above is not limited to the retroflex liquid, as it is also observed with the lateral liquid. Pairs such as petal– pedal [pεɾl̩], futile– feudal [fjuɾl̩], metal– medal [mεɾl̩] illustrate this point well.

Alveolar stops of English are produced with considerable affrication as onsets when they are followed by /ɹ̣/ (e.g. train, drain). The diacritic used for this is a _ under the stop [ṯ]. The tongue tip touches behind the alveolar ridge, exactly to the point where affricates /ʧ, ʤ/ are produced (note children’s fre quent spelling mistakes for the target train as chrain or chain).

Also noteworthy is the fact that /t, d/ may turn into palato-alveolar affricates when they are followed by the palatal glide in the following word. Thus, we get did you . . . ([dɪd ju...] or [dɪʤ ju...]), ate your dinner [etʃ jɚ dɪnɚ]).

Another characteristic of American English in informal conversational speech is the creation of homophonous productions for pairs such as planner– planter [plænɚ], canner– canter [kænɚ], winner– winter [wɪnɚ], tenor - tenter [tεnɚ]. The loss of /t/ in the second member of these pairs is also seen in many other words, as in rental, dental, renter, dented, twenty, gigantic, Toronto. In all these examples we see that the /t/ that is lost is following a /n/. However, that such an environment is not a guarantee of this process is revealed by examples such as contain, interred, entwined, in which /t/ following an /n/ cannot be deleted. The difference between these words and the earlier ones is that /t/ is deleted only in an unstressed syllable.

Finally, mention should be made of the glottal stop or the preglottalized /t/ and the contexts in which it manifests itself. A glottal stop is the sound that occurs when the vocal cords are held tightly together. In most speakers of American and British English (AE, BE), glottal stops or the preglottalized /t/ are commonly found as allophones of /t/ in words such as Batman [bæʔmæn], Hitler [hɪʔlɚ], atlas [æʔləs], Atlanta [əʔlæntə], he hit me [hihɪʔmi], eat well [iʔwεl], hot water [hɑʔwɑɾɚ]. While the glottal stop can replace the /t/ in these words, it is not allowed in atrocious [ətɹ̣oʃəs] (not *[əʔɹ̣oʃəs]), attraction [ətɹ̣ækʃən] (not *[əʔɹ̣ækʃən]; the asterisk here means “wrong” or “unattested”). The reason for this is that the glottal stop replacement requires the target /t/ to be in a syllable-final position ([bæʔ.mæn], [əʔ.læn.tə]). The words that do not allow the replacement have their /t/ in the onset position ([ə.tɹ̣o.ʃəs], [ə.tɹ̣ æk.ʃən]), as /tɹ̣/ is a permissible onset in English. We should point out, however, that /t ɹ̣ / being permissible is not carried over across words, as the compound court-room illustrates. The expected production of this sequence is with a glottal replacement, [kɔɹ̣ʔrum], because the syllabification is not [kɔɹ̣.tɹ̣um]. The glottal stop replacement of syllable-final /t/ is also observable before syllabic nasals (e.g. beaten [biʔn̩], kitten [kɪʔn̩]). The process under discussion is most easily perceived after short vowels (e.g. put, hit), and least obvious after consonants (e.g. belt, sent). As pointed out above, in absolute final position, some speakers do not replace the /t/ with a glottal stop entirely, but insert a glottal stop before /t/, as in hit [hɪʔt] (‘preglottalization’ or ‘glottal reinforcement’). The only difference between a glottal stop and a glottally reinforced [ʔt] is that the tip of the tongue makes contact with the alveolar ridge in the latter case but not in the former. It is also worth pointing out that this glottal reinforcement may be applicable to other voiceless stops for many speakers, as shown in tap [tæʔp], sack [sæʔk].

The velar stops of English, /k, g/, have appreciably different contact points in the beginnings of the following two-word sequence: car key [kaɹ̣ ki]. The initial stop of the first word is made at a significantly more back point in the velum area than that of the initial sound of the second word, which is almost making the stop closure at the hard palate. The reason for such a difference is the back/front nature of the following vowel. Thus, velars are more front when before a front vowel than when before a back vowel.

The other assimilatory process velar stops undergo relates to the different lip positions in geese and goose. While in the latter example the lips are rounded during the stop articulation, they are not so in the former. Again, the culprit is the rounded/unrounded nature of the following vowel. The stop is produced with lip rounding if it is followed by a rounded vowel. Putting together the two assimilatory processes we have just discussed, we can see why the velar stops in the sequence keep cool are produced differently. Predictably, the /k/ of the first word, followed by /i/, is unrounded and more front, while that of the second word, followed by /u/, is back and rounded.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|