Count Adjectives

المؤلف:

PETER SVENONIUS

المؤلف:

PETER SVENONIUS

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P37-C2

الجزء والصفحة:

P37-C2

2025-04-02

2025-04-02

600

600

Count Adjectives

The easy parts, as it were, have been picked off: focused adjectives off the top, and idiomatic adjectives off the bottom. The resulting situation is still a far cry from accounting for the observed tendencies in adjective ordering.

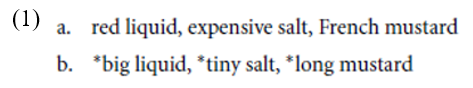

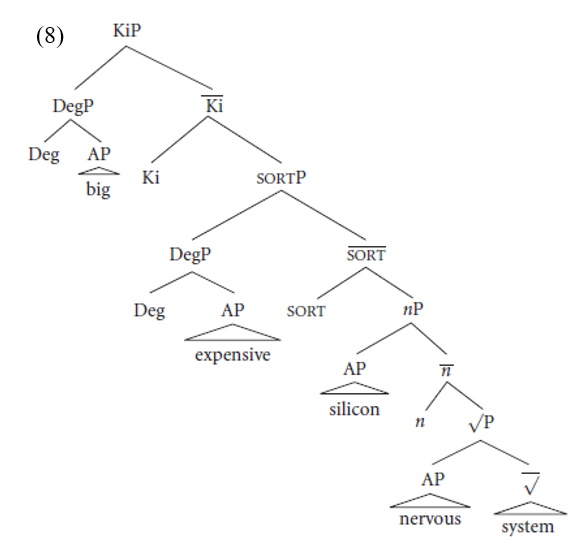

Muromatsu (2001) and Truswell (2004) argue that dimension adjectives such as big and tiny must merge above the head which creates countable entities out of masses (Borer’s Cl, Truswell’s Div, my sort). This prevents them from appearing at all with mass nouns, which lack the appropriate kind of sort.

Dimensions adjectives consistently precede color, origin, and material sdjectives.

This is explained if color, origin, and material adjective merge below sort, for example to np

As for why such adjectives merge low, I suggest the following. Modification of nP is essentially intersective. Therefore only predicates of the same semantic

type as nP can modify it. I suggest that this is the type of non-gradable predicates, including the origin reading of French, the material reading of wooden, the geometric reading of square, and so on.

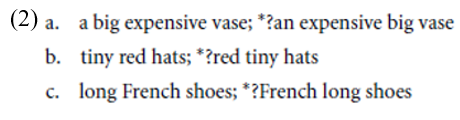

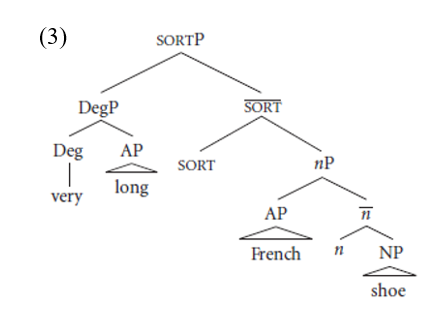

All of these adjectives can also be gradable, through combination with a Degree head (Abney 1987; Corver 1990; Grimshaw 1991; Kennedy 1999b; Svenonius and Kennedy 2006). In that case they must be interpreted in terms of a scale, which affects the way they are understood (e.g. French meaning “typical of France” rather than literally “from France,” etc.).

sortP modification occurs in a different way from nP modification: it is crucially subsective, cf. Higginbotham (1985) for example. A DegP, I suggest, can be used for subsective modification of sortP, but not a simple (nongradable) AP.

Thus I concur with Scott (2002) when he argues that APs in general are permitted to merge in whatever position makes sense for their interpretation. For example, when French is an evaluative adjective, as in a very French attitude rather than an origin adjective, the same lexeme Frenchmight be merged in a higher position.

Where I break with Scott, however, is in the fine-grainedness of the structure supporting the adjectival modification. I have suggested here that the independently motivated layers of the DP provide several different parameters of adjectival meaning (focused, count, subsective, idiomatic), and that gradability provides another parameter of meaning. These factors, combined, should account for the adjectival orderings which are actually observed, and extralinguistic factors should account for the rest. On the account proposed here, it is difficult to see how, for example, length and width could be distinct functional heads. Scott proposes these in order to account for the pattern in (4).

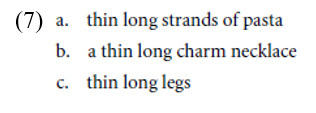

However, the solution seems too tailored to the example. Consider the examples in (5) – (6), where thick is presumably an adjective of width and lengthy presumably an adjective of length.

Scott’s proposed hierarchy does not seem to admit the necessary flexibility. Even thin long is not completely impossible.

Suppose, with Kayne (1994), that each head supports at most one specifier. If that is the case, then there cannot be more than one modifier per functional head in the DP (as suggested by Cinque 1994). This would mean that the possibilities for attachment reduce as more adjectives are added. For example, perhaps big can in principle attach to sortP, but if some other adjective is attached there, then big, if introduced, must attach either above or below.

This would produce rather constrained orders while, I believe, permitting a great deal of the actually observed variation. A language like English does seem to allow multiple instantiations of the same category, as in brave clever man ∼ clever braveman, discussed by Dixon (1977) (cf. also discussion of this example in Scott 2002). On the view taken here, this would require a language-specific innovation, perhaps the innovation of a particular functional head. Principles of economy might favor fitting adjectives into the independently motivated structure when possible, leading to favored orders but admitting reverse orders when motivated.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة