Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Gender marking

المؤلف:

P. John McWhorter

المصدر:

The Story of Human Language

الجزء والصفحة:

49-23

2024-01-19

1063

Gender marking

A. In European and many other languages, nouns are divided into gender classes. Spanish has masculine and feminine, marked with an article and often with the final vowel: el sombrero, la casa. German has three: “the spoon,” “the fork,” and “the knife” are der Löffel, die Gabel, and das Messer. This is not necessary in a language: it is an accident of history.

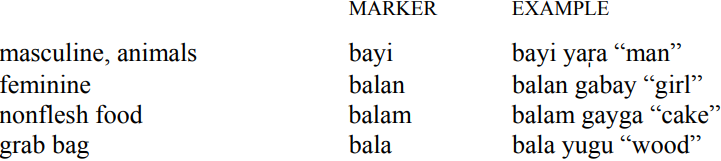

B. Stage one. In many languages, we can see how this marking begins. In Dyirbal, spoken in Australia, all nouns must be preceded by a separate word. Which word a noun takes depends on which of four categories it fits into. One is for males and animals, another for female things, another for food that is not flesh, and another is the grab bag.

Dyirbal gender classifiers:

C. Stage two. Over time, separate words such as these erode and become prefixes or suffixes—grammaticalization again. At first, the new prefixes or suffixes still correspond fairly well to categories. Swahili is at this stage. Swahili has seven “genders” (although because sex is not one of the categories marked, linguists call them noun classes). The one with an m- prefix contains people: mtu, “man”; mtoto, “child.” The one with an n- prefix contains animals: ndege, “bird”; nzige, “locust.”

D. Stage three. But as time goes on, sound change, cultural changes, eccentric semantic switches (such as the one that made the word for sister-in-law masculine in Proto-Indo-European), and other processes make the correspondence between marker and category increasingly vague. European languages are an example of this stage, where only marking actual male beings masculine and actual female beings feminine makes any immediate sense anymore.

Thus, a great deal of what a language’s grammar pays attention to is technically a kind of window dressing. Keep in mind that there are actually some languages that do not mark tense at all, and some where I and we are the same word, he and they are the same word, and so on, because pronouns mark person but not number! This shows that it is inherent to human language to overelaborate.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)